The Turkish & Islamic art

Seljuk Turks and Ottoman Empire represents an impressive longevity, combined with an immense territory (stretching from Anatolia to Tunisia), which led naturally to a vital and distinctive art, including plentiful architecture, mass production of ceramics (most notably Iznik ware), an important jeweler’s art, Turkish paper marbling Ebru, Turkish carpets as well as tapestries and an exceptional art of manuscript illumination, with multiple influences.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

SELJUKS AND OTTOMAN

The Seljuks, nomads of Turkic origin from present-day Mongolia, appeared on the stage of Islamic history toward the end of the 10th century. Architecture and objects were synthesized various styles, both Iranian and Syrian. The art of woodworking was cultivated, and at least one illustrated manuscript dates to this period. Caravanserais dotted the major trade routes across the region, placed at intervals of a day’s travel. The construction of these caravanserai inns improved in scale, fortification, and replicability. Also, they began to contain central mosques.

Starting in the 13th century, Anatolia was dominated by small Turkmen dynasties, which progressively chipped away at Byzantine territory. The Ottoman Empire, whose origins lie in the 14th century, continued in existence until shortly after World War I. This impressive longevity, combined with an immense territory (stretching from Anatolia to Tunisia), led naturally to a vital and distinctive art, including plentiful architecture, mass production of ceramics (most notably Iznik ware), an important jeweler’s art, Turkish paper marbling Ebru, Turkish carpets as well as tapestries and an exceptional art of manuscript illumination, with multiple influences.

ARCHITECTURE

Reference and Source:

* E. Akurgal. The Art and Architecture of Turks., NY: Rizzoli International Publications, 1980; Önder Küçükerman, Anadolu Mirasında Türk Evleri. İstanbul, 1995.)

* (c) Copyright 2010 Turkish Cultural Foundation

* Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism

MOSQUES

The oldest mosque within the borders of Turkey is the Ulu Cami (Great Mosque) of Diyarbakir, dating back to the seventh century with several later restorations. Other early great mosques are in Urfa, Cizre, Silvan, Mardin, Kiziltepe, Bitlis, Harput, Niksar, and Kayseri. Probably the most important Seljuk work is the Old Mosque in Konya, dating back to 1155. For several centuries, the Seljuk mosques were of the basilica type with the Great Mosque of Divrigi providing a superb example. The style then transitioned from square volume to circular ones like a dome, squinches or bands of triangles.

KULLIYE

Two important innovations to the development of Ottoman architecture from this period are kulliye (the social/religious complex) planned around the mosque and the adoption of half-dome as a major structural element for building Great Mosques. Both concepts were introduced by the complex of Fatih in Istanbul, between 1462 and 1470. The complex of Fatih consisted of a mosque, sixteen madrasahs (Koran schools), a library, a hospital (Dar us Sifa), a hostel, a public kitchen (imaret), a caravan saray, and the mausolea of Fatih Mehmet and his wife. His son Beyazit II continued in this tradition and built three complexes (Istanbul, Edirne, and Amasya). The biggest one in Edirne, built in 1484-1488, contained a mosque, two hospices, a large public kitchen, a dining hall, bakery, storehouse for food, a medical school, a hospital, a mental asylum, among other facilities.

Even a more grand and magnificent example of Ottoman architecture is Suleymaniye, in IstanbTourismul, designed and built by Architect Sinan (Koca Mimar Sinan) in only seven years starting in 1550, is the biggest and most complex masterpiece of its type.

CAREVANSERAIS

Source: Unesco.org

Seljuk Caravanserais on the route from Denizli to Dogubeyazit

The caravanserais, a new architectural type with social function developed in central Asia by the Karakhanids and Ghaznavids passed into Anatolian Turkish architecture. The institution of caravanserais has its most variations in Seljuk Anatolia, using the forms of Anatolian stone architecture. These buildings offering travellers in mountain and desert all the possibilities and comforts of civilization of the period each effectively a social fondation subject to an organized and continuous state programme, appear to present a typical characteristic of Turkish society, Denizli-Dogubeyazlt Route consists of about 40 Hans about which 10 are very well preserved. Some of these are Akhan, Ertokus Han, Saadettin Han, Obruk Han, Agzikarahan, Sultan Han (2), Oresin Han, Sikre Han, Mamahatun Caravenseria and Hacibekir Han.

Caravanserais were havens in which caravans could take shelter. They have their origins in the nomadic lifestyles of the Turkish tribes of Central Asia. At a very early period there existed a social institution called muyanl~k, a word that means “charity”, “pious deed”, and “kindsess.” These were generally simple dormitories that offered travelers food and a place to sleep. By the 7 th centruy, these simple dormitories had developed into more complex establishments called ribat, a word that may be translated as “inn.” There is evidence that hundreds of these ribats were built. The culmination of this line of development is the massive caravanserais that the Seljuks built in Anatolia. Caravanserais were huge accommodations, facilities that provided shelter, food and drink for a caravan’s full complement of people, animals, and cargo and could also handle its needs for maintenance, treatment, and care. They were arranged along trade routes at intervals that were calculated in view of the amount of distance that a caravan could be expected to cover in a single day. This distance was called menzil in Turkish, a word that means, among other things, “journey” in its archaic sense of “a day’s travel”.

On the basis of the examples remaining and other evidence, this menzil seems to have averaged about 30 kilometre the equivalent, under normal conditions, of a six-hour journey to which another two hours had to be added for arduous travel in regions like deserts. Caravanserais or their simpler cousins, khans, were always located to that a caravan could be sure of reaching one by the day’s end.

Architecture and function

Architecture is always determined by climatic and environmental conditions but never more so than in the case of caravanserais, to which the problem of security had to be added. Caravanserais in the eastern part of Anatolia for example were built like small, square castles heavily fortified with thick walls of stone. as we move westward on the other hand, they tend to be U-shaped and built of masonry and even, on occasion, of mud brick, Other differences are also apparent in such details s the sizes of individual rooms, the width of doors and windows, and the units and functional divisions they contained. Nevertheless there were certain things that every caravanserai had to have. There were certain to be baths, a masjid, a cistern o fountain, an infirmary, a cookshop, a place for the storage of provisions, and shops. Among the personnel there would certainly be a wainman, a blacksmith, a money-changer, a tailor, a cobbler, a physician, a veterinary, and so on. About 250 Anatolian caravanserais are known. Of these, eight are called sultanhan (literally “sultanis khan”) and were all built in the 13 th century. Those constructed in the early part of the century generally conford to a standard plan of a courtyard and enclosed arens covering the same amount of ground. Seven of these building bean identifying inscriptions and one does not. Some of them are still referred to by the name sultanhan who others acquired local names to distinguish them. Agzikara Han is probably one of the most important “ordinary” khans and the degree of its workmanship approches that of the royal khans. It is another of those caravanserais whose massive portal and rowers give it the appearance of a fortified castle. The double portal, free-standing masjid and domed hall, as well as the quality of its architecture, are all worthy of a true royal khan. The main portal is decorated with geometric patterns. Between the surmounting muqarnas and framing arches is a band of swastikas. The building was completed in 1237. Sultan Han On the Kayseri-Sivas road is another caravanserai with the name Sultan Han. Covering 3,900 square meters, it is the second-largest of the buildings of the group. All the distinguishing features of the Konya-Aksaray caravanserai are repeated here. The massive walls and supporting turret-towers give the building the appearance of a fortress.

HOUSES

The architecture of Turkish traditional houses is influenced by a variety of climactic and natural resources, by the traditions of earlier houses remaining in Anatolia from the Byzantine era, and by traditional Turkic culture, which was brought from Central Asia by the Turks. Local materials, both natural and inorganic, give Turkish houses their character and identity; in North Anatolia, the wooden houses from rich forests; while in Central Anatolia, the stone and sun-dried brick houses; in West Anatolia, stone; and in South Anatolia, stone and wooden houses. In conjunction with these principals, the interiors of Turkish houses were planned for different purposes, like the winter and the summer rooms. In addition, Islamic and Turkish customs played a great part in shaping the house. This factor brought on a common plan, which made Turkish houses more homogenious, though there were still climatic and regional differences.

* BEYPAZARI HOUSES

* BURDUR HOUSES

* SAFRANBOLU HOUSES

* EASTERN BLACK SEA HOUSES

* HOUSES OF A YORUK VILLAGE

* WOOD CULTURE AND TIMBER HOUSES

* USAK HOUSES

* CAPPADOCIA YUNAK HOUSES

* CUMALIKIZIK HOUSES

* HOUSES IN THE LANDS OF OTTOMAN EMPIRE IN EUROPE (RUMELIA)

* SEA MANSIONS (YALI)

PALACES

Of the earlier great palaces of Ottoman sultans, only Topkapi palace and some kiosks remain. The Edirne Palace, second only to Topkapi, was destroyed in the 19th century. European styles influenced the Ottoman architecture after the second half of the nineteenth century. The palace of Dolmabahce, Beylerbeyi, Ciragan can be mentioned as examples of European influence.

Reference: E. Akurgal. The Art and Architecture of Turks, Rizzoli International Publications, NY, 1980.

FOUNTAINS

Endowing money for the construction of a fountain and a water supply line to it was an act of piety which played an important role in Ottoman life. The sultan, sultan’s mother, sultan’s daughter, grand vezirs built fountains in expression of their economic, social and political standing, and fountains became an important part of the architectural tradition. Fountains were decorative features of both outdoor public spaces like squares, and intimate indoor spaces in private dwellings, and they reflected the architectural taste and styles of their time.

A fountain as well as a coffee house and spreading plane tree casting welcome shade. Fountains were diverse, both as regards their structures and their functions, and twentieth century writers on the subject have classified them in numerous different ways. Often the name of a fountain tells its own story.

OLD TURKISH BRIDGES

Examples of Ottoman and Seljuk structures such as stone bridges are spread over three continents, representing many centuries long Turkish heritage and culture over vast areas of these empires. Some of them still survive today.

THE TURKISH BATH

In Central Asia, the Turks had steam baths which they called ‘manchu’. Bringing their Asian tradition with them, they merged it with the Roman bath culture they found in Anatolia, and a new synthesis was born, the ‘Turkish bath’. With their traditions, arts, associated beliefs, and philosophy of life, baths became an institution, which spread all the way from Anatolia to Hungary in Europe. (Reference: Sabiha Tansug/Servet Dilber)

THE GREAT ARCHITECT SINAN (KOCA MIMAR SINAN)

Sinan is considered the greatest Ottoman architect of the Ottoman Empire’s Architectural heritage. It is generally assumed that Sinan was born in the year 1490. He travels widely throughout the empire, as far as Baghdad, Damascus, Persia and Egypt. In his own words he informs us about his observations: “I saw the monuments, the great ancient remains. From every ruin I learned, from every building I absorbed something.”

By mid-life Sinan acquires a reputation as a valued military engineer and is brought to the attention of Sultan Suleyman (1520-66) who in 1537 appoints Sinan (aged fifty) as head of the office of royal architects.

Challenged by the works of his predecessors and the majesty of Hagia Sophia, Sinan creates the Sehzade Mosque, one of his first masterpieces and is considered one of the most remarkable of buildings to this day.

The legendary stature of Suleyman is realized in what is commonly called the “crown on the hill”. Dominating the Bosporus and the Golden Horn, the silhouette of the Suleymaniye, with its slender minarets and lofty dome, is one of the defining features of Istanbul. Almost 10 years in the making, Sinan master plans, designs and builds the “Suleymaniye Kulliye” . The Kulliye covers almost 25 acres and includes in addition to the large mosque (basilica plan), four schools (medreses), a hospice, public baths (hamam), a hospital & dispensary, bookshops, a library, the Sultans’ tomb (turbe) and the worlds first teaching asylum (bimarhane). One of the truly unique urban Mosque and charitable building project is the Sokollu Mehmet Pasha Mosque Complex (1571-72) in the Kadirga Liman quarter, location of the former gate (Kumkapi), which protected the harbor.

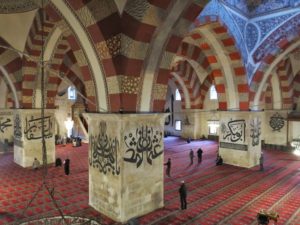

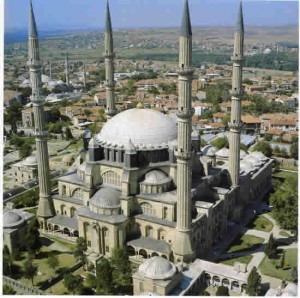

During the construction of the Sokollu Sinan receives a great deal of pressure from Sultan Selim II, son and successor to Sultan Suleyman, to progress what is to be Sinan’s monumental masterpiece, The Selimiye Complex in Edirne (1568-74). The pencil-shaped minarets, grooved to express verticality, are some of the tallest ever built (230 feet from ground to finial).. Edirne has suffered through many earthquakes but none have harmed this monument. Sinan’s crowning glory is summed up in this project through its graceful synthesis of the exterior with and ideal spatial interior.

The few prominent projects presented here represent only a small part of this great architect’s voluminous design and construction accomplishments throughout the Empire. It is believed that Sinan’s total works encompass over 360 structures which included 84 major mosques, 51 small mosques (mescit), 57 religious schools (medreses), 7 seminaries, 22 mausoleums (turbe) 17 care facility, 3 asylums, 7 aqueducts, 46 inns, 35 palaces and mansions and 42 public baths.

Sinan died in 1588 and was buried in a modest tomb, which he designed for himself at the rear of his garden near the Suleymaniye Mosque in Istanbul

(Reference: Stierlin, Henri, Turkey From the Seljuk’s to the Ottomans, Koln: Tascen, 1998.)

FINE ARTS AND HANDICRAFTS

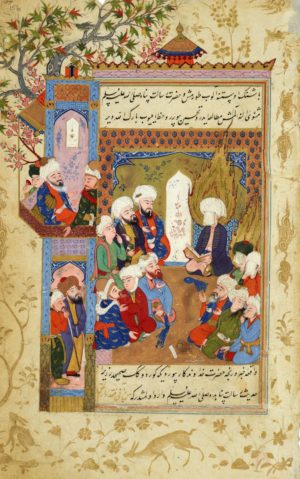

MINIATURES

The eight and nineth century paintings found at Chotcho, there capital in Turfan, are the earliest examples of Turkish book illustrations known. Although numerous wall paintings can still be seen, very few book illustrations still exist. The people in these miniatures, especially male figures, have portrait quality, with their names inscribed below. After these earliest examples, there was almost four centuries of time gap, which no book illustrations survived, until the preiod of the Suljuks in Anatolia. However the figrues seen in Seljuk art still show the tradition of Uighur paintings. The minatures illustrate a fantasy world of demons, evil spirtis and sceens from nomadic life. There are also other Seljuk works in different styles showing evidence of Byzantian influence.

It was during the reign of Suleyman the Magnificent (1520 – 1566) that Ottoman miniature painting developed its identifiable style. Even though the various influences continued to be felt, the true characteristics of Ottoman painting begins to appear due to the existence of Turkish artist trained in the palace studios. This was the style of an empire absorbing vast territories on its eastern and western frontiers, and merging the influence of Turkoman, Persian and western art.

The Sultans and elite who patronized this often representational art, kept their paintings for private viewing, fearful of the religious zeal of the public. Miniature painters were divided into two categories; those who painted decorative murals and flowers, and the smaller number, many of whom were non-Muslims, who painted portraits, sieges and battle-scenes. Turkish miniatures are not as famous as Persian ones, although they are often more moving and powerful, due to the stronger shades used and to a greater attention to detail.

Reference:

* Atasoy, Nurhan and Cagman, Filiz. Turkish Miniature Painting. Istanbul: RCD Cultural Institute, 1974.

* Turkish official tourism portal

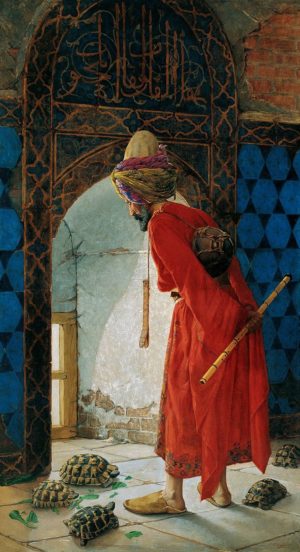

PAINTING

Turkish painting in the western sense only began in the 19th century, with the founding by Osman Hamdi Bey, himself an accomplished painter, of the Academy of Fine Arts. Turkish painters were sent to France and Italy by the Sultan, and foreign painters, mostly Italian, were brought from Europe to transfer their skills. Today this academy is known as Mimar Sinan University. The most famous of the early Ottoman painters are Osman Hamdi Bey, Seker Ahmet Pasha, Hoca Ali Riza, Sevket Dag , Ahmet Ziya and Halil Pasha. In 1919 the Ottoman Society of Painters held their first exhibition in Galatasaray.

CALLIGRAPHY

Turkish calligraphy is a unique artistic creation although calligraphy itself is not of Turkish origin. Ottomans adopted it with religious fervor and inspiration, taking this art to its pinacle over a five hundred year period. Sultan Mehmet the Conqueror, introduced major changes in the traditional seven writing styles and put the mark of the Turkish national character on Islamic writing. His followers further improved Turkish calligraphy over the centuries. Hafiz Osman, Mustafa Rakim, Yesari Mehmet, Sevki Efendi, Sefik Bey, Mahmut Celaleddin, Kadiasker Mustafa Izzet, Sultan Mahmut II, Aziz Efendi, Necmettin Efendi, Sami Efendi and Hamid Aytac are all noted Turkish calligraphists who contributed to the development of this art.

Turkish calligraphists have always made the paper, pens and ink they used. The paper used to be painted with natural dyes. Then it was polished with boiled starch and egg white. The paper dressed in this way allowed for easily correcting mistakes. Pens were made of hard reeds. Bigger pens (known as “celi”) were made of wood. To produce ink, the calligraphists used to burn materials such as pine and linseed oils. Please see Writing Tools folder for the materials and tools used.

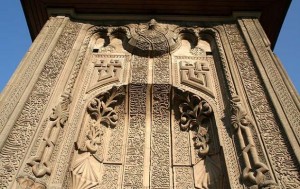

STONE CARVING

Stone and wood were the main contruction material in Anatolian Turkish culture. Carved decorations in the form of figural and ornamental compositions appeared on mosques, madrasahs, turbes, tombstones, and caravan sarays. By the thirteen century designs moved towards more complex and intricate decorations and embroidery-like low reliefs with dense geometrical interlace angular motifs, Kufi inscriptions. In the eighteenth century, stone decorations were largely replaced by stucco interior decorations, Barok interlace and motifs, as intensive Westernizations took place.

Religious rulings issued only in the ninth century discouraged the representation of any living beings capable of movement but they were not rigidly enforced until the fifteenth century. Figural art is especially rich in stone and stucco reliefs of the Seljuk period, adorning both secular and religious reliefs and tiles. The subjects included nobility as well as servants, subjects, hunters and hunting animals, trees, birds, sphinxes, lions, sirens, dragons and double-headed eagles. Some of the symbols are proof that shamanistic religious beliefs survived. The eagle was regarded, for example, as a holy bird, a protective spirit, and the guardian of heaven. It was also a symbol of potency and fertility. Eagles on tombstones or turbes reflect shamanistic beliefs that the souls of the dead rose up to Heaven in the form of birds. In Seljuk architecture, small human heads are sometimes scattered among arabesques.

TURKISH TILE MAKING

We have enclosed an article “The Art of Turkish Tiles And Ceramics” written by Associate Professor Dr. Sitare Turan Bakir from Mimar Sinan University, Department of Traditional Turkish Arts. If you are interested in learning more about Turkish Tiles, you can visit this link.

“To summarize, the art of Turkish tile and ceramic-making developed over the centuries incorporating many different techniques and styles. Enriched by the arrival of the Seljuks, the ceramic industry in Anatolia achieved a deservedly worldwide reputation with the support of the Ottoman court. Today, Kutahya has been revived as an important center of tile and ceramic-making. In addition, efforts are also being made in private workshops and educational institutions in Iznik, Istanbul, and Bursa to keep the art of traditional Turkish tiles and ceramics alive and develop it so that it can address the demands of modern-day life.”

WOODCARVING AND WOOD ARTWORK

Seljuk Turks excelled in the working of stone and wood. The most important of the woodworking techniques was called kundekari where pieces of shaped wood are interlocked through rabbeting and mortising, without the use of any nails or glue. Anatolian Seljuk wood workmanship produced its most mature examples in both quantity and quality by combining the styles and techniques brought by the Turks to Anatolia with local styles of decoration in a new synthesis. A rich decorative style is observed in this period, consisting of floral and geometric designs, inscriptions and, albeit fewer in number, figural images as well. In Anatolian Seljuk wood workmanship, carving is the technique most appropriate to, and most frequently employed for, the decorative style in which thuluth inscriptions and palmette and half-palmette motifs are often used amid rumî branches and tendrils. Decorations incorporating geometric patterns also occupy an important place in Seljuk wood workmanship.

The art of woodworking, which is observed both in architecture and on decorative objects, produced some of its most beautiful examples in the Ottoman period. We see it in architecture in columns and beams; as decorative elements on doors and shutters, pulpits, mosque niches, ceiling ornaments, and balcony railings; on furniture such as lecterns, Koran stands, turban stands, trousseau chests and tables, and as accessories.

The Rococo style, which arose as a style of architectural decoration in the palaces of France in the mid-19th century, also exhibits its influence in Ottoman wood workmanship, as in every branch of Ottoman art, as ‘Turkish Rococo’. On small-scale handicrafts, the classical Ottoman decorative motifs give way to floral bouquets, represented naturalistically in a vase, acanthus leaves, C- and S-curving branches, ribbons and bows.

Unable to withstand the ravages of time, most objects made of wood have failed to survive to our day. Nevertheless, you may still see some of the finest examples of wood workmanship from the 8th up to the end of the 19th century in the Museum of Turkish and Islamic Art.

Reference:

* Gonul Tekeli, Ali Konyali/SKYLIFE

* Copyright 2010 Turkish Cultural Foundation

MOTHER OF PEARL AS AN ART FORM

The shining, playful, and reflected light of mother of pearl has attracted the attention of human beings since the beginning of the world. Societies, tribes, and nations have all added the technology of their day to their experience, knowledge, and understanding, and they have turned mother of pearl from one form into another. Though mother of pearl is quite widespread around the world, its assumption of the aspect of a magnificent branch of the arts after a past of many centuries began when it came into the hands of the Ottoman Turks.

Although there is no evidence to document the use of mother of pearl among the Turks of Central Asia, the existence of such objects is mentioned in Marco Polo and in the memoirs of several Byzantine ambassadors. In addition it is known that the Kazan Tatars made calligraphic inscriptions in mother of pearl.

The art of mother of pearl working is a branch of the arts which is intimately involved with wood. One needs to chose the appropriate wood according to the method of the work to be done. In the inlaying method, one uses walnut, which is suitable for carving and does not become brittle upon carving. In the gluing method on the other hand, the wood must be of an even-tempered nature. Linden, which is unaffected by heat or cold, and which maintains the same straightness for years -ever centuries- is the wood most suited for this technique. In the gluing technique, the surface may be covered entirely in mother of pearl, or else, auxiliary materials may be used together with it.

Source:

* Antika, The Turkish Journal of Collectable Art-October 1986 issue: 19

* Turkish Cultural Foundation

MARBLING (EBRU)

Paper marbling is a method of aqueous surface design, which can produce patterns similar to marble or other stone, hence the name. The patterns are the result of color floated on either plain water or a viscous solution known as size, and then carefully transferred to a sheet of paper (or other surfaces such as fabric). This decorative material has been used to cover a variety of surfaces for several centuries. It is often employed as a writing surface for calligraphy, and especially book covers and endpapers in bookbinding and stationery. Part of its appeal is that each print is a unique monotype.

The current Turkish tradition of ebru dates to the mid 19th century, with a series of masters associated with a branch of the Naqshbandi Sufi order based at what is known as the Özbekler Tekkesi, located in Sultantepe, near Üsküdar. The founder of this line is accredited to Sadık Effendi (d. 1846). It is said that he learned the art in Bukhara and taught it to his sons Edhem and Salıh. Based upon this, many Turkish marblers have stated that the art was perpetuated by Sufis for centuries, although evidence for this claim is has never been concretely established. “Hezarfen” Edhem Effendi (d. 1904) is attributed with developing the art as a kind of cottage industry for the tekke, to supply Istanbul’s burgeoning printing industry with the decorative paper. It is said that the papers were tied into bundles and sold by weight. Many of these papers were of the neftli design, made with turpentine, an equivalent to what is called stormont in English.

The premier student of Edhem Effendi was Necmeddin Okyay (1885-1976). He was the first to teach the art at the Fine Arts Academy in Istanbul. He is famous for the development of floral styles of marbling, in addition to yazılı ebru a method of writing traditional calligraphy using a gum-resist method in conjunction with ebru. Okyay’s premier student was Mustafa Düzgünman (1920-1990), the teacher of many contemporary marblers in Turkey today. He is known for codifying the traditional repertoire of patterns, to which he only added a floral daisy design, in the manner of his teacher.

Source: Wikimedia the Free Encyclopedia

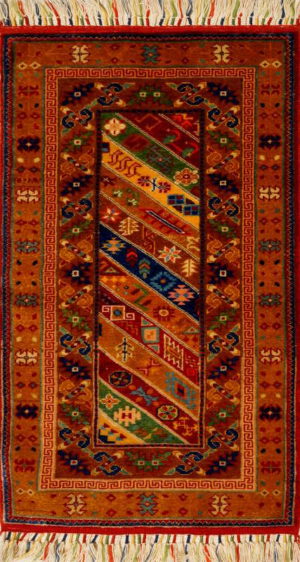

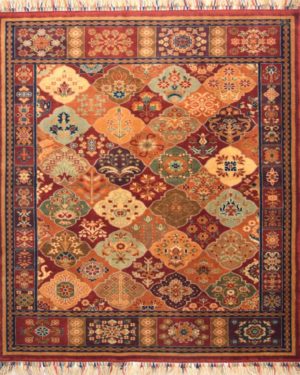

ANATOLIAN CARPETS

Carpet weaving is the traditional art of Turks and the development of the arts linked to the Turks since its inception, with early woven fragments discovered in Central Asia. The knotted rug appears to have spread from Central Asia westwards through Persia and Anatolia with growing Turkish empires. Floor rugs have been known since ancient times going back to Assyrians and Babylonians but these were not knotted rugs but woven fabrics. The knotted carpet does not appear in Islamic countries until the emergence of the Seljuks in the 11th century.

The Seljuk rugs found at Konya, capital of Anatolian Seljuks, are knotted in the Turkish – Ghiordes knot, in the same style as the carpet fragments found in tombs in the Altai mountains. (Hermitage Museum, Leningrad). Seljuk carpets can be characterized by geometric and stylized floriated motifs in repeating rows and by Kufic inscription border patterns.

By the beginning of the 14th century, animal figures emerged in Turkish rugs. By the 16th century, the medallion motifs and the diverse foliate compositions had taken over, as the influences of the expanding Ottoman territories and the Iranian and Mamluke art were felt. The period claims two major groups of rugs; the Usak rugs with the essential motif of a medallion and the Ottoman court rugs with naturalistic motifs.

The Ottoman court rugs used the Iranian Senna knot, in order to accommodate the very fine and detailed floriated designs and the clusters of Turkish flowers – the tulip, hyacinth, carnation, rose, and the blossoming branches. Ottoman court rugs also started to use silk in the warp and the weft on the looms of Istanbul and Bursa. In 1831, the first carpet factory with 100 looms was opened by Abdulhamid II at Kereke and even today, rugs in Anatolia, especially around Kayseri, Sivas, Konya, Kars, Isparta follow the traditional patterns of this truly Turkish art.

Although the history of carpets can be traced back to ancient times that is to the Turks who lived in Central Asia, the knotted pile carpet spread with the rise of the Seljuk Turks of Anatolia in the 11th century. New motifs and techniques developed rapidly, producing a rich variety of rugs throughout the many Turkish carpet weaving regions. Apart from carpets peculiar to such regions as Usak and Bergama, and those representing different periods of Turkish history, there are still other types based on motif and technique. These include carpets bearing animal motifs, the Holbein-type rug (Turkish rugs which appear in the works of Flemish painters), and the Ottoman palace carpets. Hereke carpets belong to the last category.

Hereke carpets are known primarily for their fine weave. Silk thread or fine wool yarn and occasionally gold, silver and cotton thread are used in their production. Wool carpets produced for the palace had 60-65 knots per square centimeter, while silk carpets had 80-100 knots. The knots were of two main types: the “hekim” knot and the Turkish or Gordes knot. After each row is woven, a length of yarn is passed through it and this single-warp knot creates the denser knotting which permits finer and more intricate designs to be created. In some of the carpets, a relief effect is obtained by clipping the pile unevenly.

Source: Yetkin, Serare. Historical Turkish Carpets. Istanbul: Turkiye Is Bankasi, 1981.

>> See also “Understanding the language of Anatolian Rugs and Kilims”